Introduction

Language!

At 19, I was ready to enter university. I was going to study Hispanic Philology. I know—hardly the most market-oriented choice. But I had always been a literature fanatic. However, I had never studied Linguistics, the other pillar of Philology. In fact, I was still monolingual. My (generously speaking) barely B1 English level couldn’t earn me the title of bilingual.

Ten years later, my girlfriend asked me (just a few weeks ago) why I didn’t add Latin as the seventh language in my repertoire. She asked me in the main language we use in our relationship—English. Sometimes, we use French, and on rare occasions, Spanish. I use four languages daily: Spanish, English, Interlingua, and French. Every week, I consume content in Italian and, to a lesser extent, in Portuguese.

At 19, I was just a monolingual poetry enthusiast. Today, I speak six languages, I’m a philologist, and I make a living teaching languages.

Want to know how I made it possible?

My first steps: English

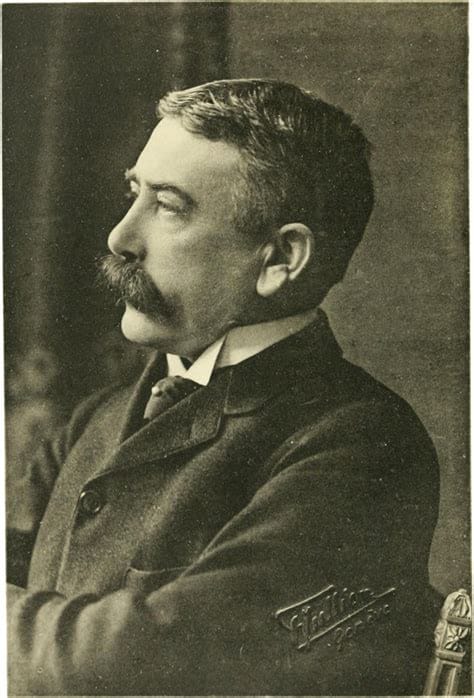

That summer, ten years ago, I became aware of the connection between literature and linguistics (I know—wow, what an epiphany). So, I decided to start with what I had read was the foundational book of modern linguistics: Cours de Linguistique Générale (at the time, I read it in Spanish: Curso de Lingüística General), by the Swiss scholar Ferdinand de Saussure.

But… as a modern man, as a 21st-century philologist, I couldn’t just know the theory. How on Earth did I expect to be a philologist in today’s world without speaking English!?

Since I had already become an «autonomous learner,» at least I was able to consume content in English on my own.

My financial situation was far from ideal, so I couldn’t afford to pay for a teacher. Plus, I had no one to practice with—though, to be fair, that wouldn’t have been too hard, since I lived in a fairly international city, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. This limited my options.

Fortunately, I had the only thing truly necessary to learn a language in our times: a smartphone with Internet access.

I started to read in English

about the topics that fascinated me (and still do): economics and Christianity. Like so many others before me, I discovered an essential principle of language learning. The majority of it—especially when learning autonomously and particularly in the beginning—relies on massive exposure to content in the target language.

Although I don’t strictly follow Krashen’s principles (which is a great topic for debate, but I’ll save that for a future article), it does seem that Pareto’s principle can be applied to language learning. Eighty percent of the time (or effort) spent learning a language should be dedicated to consuming it—whether through reading, music, or film.

Since then, I’ve structured three-quarters of my language learning time this way. I choose a topic that interests me and research it in the language I’m learning. I listen to podcasts, watch YouTube videos, or read endlessly.

Evidently…

This doesn’t mean that output should disappear or be ignored. If you want to learn to ride a bike, you have to ride a bike. Likewise, if you want to learn to speak a foreign language, you have to speak it.

And yes, I still feel a bit nervous when speaking a language I haven’t fully mastered—but I always remind myself: every mistake is an opportunity to learn.

I remember talking to a Polish Erasmus student at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. I was explaining something about one of the classes I was attending at the time—Semantics. And when he asked me what Semantics studies, I learned, after making a mistake, a key syntactic difference between Spanish and English.

La semántica es el estudio del significado = The Semantics is the study of the meaning

Right? Wrong! There isn’t a set of different “Semantics” or a set of different “meanings” to choose from. So, in English, we don’t use a definite article: Semantics is the study of meaning. I never make that mistake anymore.

Don’t be afraid to make mistakes! Embrace them!

A special case: Interlingua

That same summer, while reading on Wikipedia about the great and almost unparalleled J. R. R. Tolkien to practice my English reading skills, I came across something in which the British writer was also, in a way, a pioneer: constructed or artificial languages.

Among these languages, there is a subcategory known as «auxiliary languages,» which are created to somehow facilitate international communication, either from a grammatical or ideological perspective. The most famous example of this subcategory is Esperanto. Others include Ido (a descendant of Esperanto), Medžuslovjansky (also called «Intereslavic»), and Interlingua.

The latter can be described as a simplified Romance intermediate language, inspired by the grammar of modern English, so we could also define it as an Anglo-Romance language. In this way, it possesses the musicality and elegance of Romance languages and the grammatical simplicity of English. Allow me to show you an example:

Mi nomine es Eduardo Ortega e io scribe un articulo re multilinguismo.

This beauty and simplicity caught my attention from the very first moment, and I dedicated myself to learning it, while simultaneously deepening and improving my command of Shakespeare’s language.

Though ideologically, this language was constructed to become an auxiliary language, I prefer to categorize it within the group of zonal languages—those shaped from a family or branch of languages. In the case of Interlingua, from the Romance branch of the Indo-European family.

Why? Because I believe its greatest advantage lies elsewhere, in its immense propedeutic capabilities. Learning Interlingua facilitates the learning of other languages, especially Romance ones.

More languages: Italian and Portuguese

After that year when I learned English and Interlingua, I thought I wouldn’t learn any other languages. Becoming a polyglot wasn’t on my mind. I wanted to learn English because I refused to be a monolingual philologist and because of its status as a global language, and I chose Interlingua for its simplicity, beauty, and elegance.

Unfortunately—or fortunately—the world had different plans for me. Being, as I was (and still am), a hopeless fan of Spanish Golden Age poetry, I was familiar with the influence of two great Italian poets, Petrarch and Dante. Eventually, I was able to read Petrarch’s Canzoniere and later Dante’s Vita Nuova. This year, after acquiring beautiful editions of the Divina Commedia in its original language both in France and in Florence, Dante’s hometown, it’s time to read the great magnum opus of Dante.

Beyond literature, learning Italian has allowed me to understand more deeply the sensitivity and cultural richness of the Renaissance world, teaching me that each language is a unique window into the soul of those who speak it.

But the story doesn’t end there. Just three months later, after being in constant contact with Brazilians in Interlinguistan (a term I coined to refer to Interlingua speakers scattered around the world, which has gained some popularity), I decided to learn Portuguese as well, though it has never been as serious a dedication as the other languages. Even so, just a few months ago, after more than two years without speaking the language, I happily discovered that I was able to maintain a decent conversation in Portuguese with a coworker from Portugal.

Mesmo que eu esteja um pouco enferrujado.

Migrating to France

Then I thought, «Alright. Now I’m serious about becoming a polyglot. How exciting it is to learn new languages! What should be the next language? The only thing I know for sure is that it won’t be another Romance language. I need to explore something more distant.»

Once again, for better or for worse, the world had other plans for me. In the still financially difficult situation I found myself in, I couldn’t say no to a job offer in France, in the southeastern region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.

I remember the mixture of excitement and dizziness I felt upon arriving in France. Everything was new: the landscape, the customs, and, above all, the language. I didn’t speak French fluently, and although my job was in English, every daily interaction became a small challenge. How do you ask for directions to get somewhere (it’s terrifying to realize that Google Maps doesn’t work when you’re abroad and don’t know the language)? How do you ask for a hot chocolate without feeling awkward? It was then that I understood that learning a language isn’t just about adding words to your vocabulary; it’s about learning to live in another world.

But…

The world, in its planning for me, had intended to make me learn French and wasn’t going to give up easily. So, a year later, still working with the same company, it placed in my path a French woman who captured my heart and became my life partner.

Finally, the sixth language was another Romance one (or another romance?): French. As with the other Romance languages, I leveraged my prior knowledge of related languages to speed up the learning process. And, like with the other languages I had learned, I decided to dedicate the majority of my linguistic effort to consuming content in the language, not only to learn grammatically, but also to acquire its culture.

Unlike the other languages, French had an added difficulty, which wasn’t grammar or vocabulary—both of which I almost already possessed, thanks to the other languages. No, the difficulty of French lies in its phonological system.

Why do you need so many vowels, Victor Hugo!

Learning Strategies

As I continue learning languages, I reaffirm a principle I’ve mentioned before: most of the time should be dedicated to consuming the language. In my case, I consume more written content, as I’m a fan of literature. I can say that I’ve read authors like Tolkien, Shakespeare, Petrarch, Dante, and Camus in their native languages. In fact, these days I’m tackling my second book by the latter author, Le premier homme, to keep acquiring new vocabulary in my sixth language, French.

Furthermore, I’ve used

leverage

to learn more quickly. This is about leveraging the common elements between the languages we know to learn more rapidly the one we want to study. The simplest example here is shared vocabulary, often cognates (words in two different languages that come from the same origin: like the Latin vitam, which gave vida in Spanish and Portuguese, vita in Italian and Interlingua, vie in French, and in its adjectival form, vital in English). But we can also use it with grammar. For example, in Spanish, we don’t say *quiero que vienes, we say quiero que vengas. Similarly, in French:

je veux que tu viennes

where the verb venir also takes the subjunctive form.

This input or consumption of material in the target language must be material created for natives. No matter how scary it might feel, our minds will eventually adapt quickly to what we’re really going to encounter in real life.

This doesn’t mean you should choose something you won’t understand at all. Of course, the material must be intelligible to some extent; otherwise, you wouldn’t be able to learn. But forget about those school listenings or textbook writings (or at least don’t rely on them as your main source of input).

This also has another very important advantage: you won’t just be consuming the language as a grammatical entity, but you’ll immerse yourself in the culture. If you can’t afford immersion in the country, immerse yourself in the language through massive consumption of content in that language, while gradually absorbing the gestures, references, and humor of its speakers.

Beyond my degrees (in relation to languages

I am a philologist specialized in linguistic didactics)

my repertoire of languages is a testament to what it’s like to be on the student’s side. I’m still a student every day! That’s why I understand my students’ challenges, and it allows me to help them overcome any obstacle they may face.

Moreover, as I add languages to my repertoire, I can mentor more students. For example, when teaching English to French children, I was able to use my knowledge of French to clarify complex grammatical structures by comparing them with their native language. Similarly, while teaching Interlingua to a Czech gentleman who speaks English and Esperanto, I used the similarities between these languages to facilitate his understanding and accelerate his learning. In both cases, I was also able to identify the source of linguistic interference, by noticing French structures in English or Esperanto vocabulary that doesn’t exist in Interlingua.

It’s a marvel to have been able to turn my passion for languages into my profession and to be in constant contact with people who share similar interests. We’ll talk in another article about the economic benefits of speaking a second language. Something we all know without the data, but the data shows something interesting. Stay tuned.

In conclusion

I’ve always found it very difficult to explain to someone the difference that knowing another language makes. When you are immersed in the culture, the simple transposition of words from the language you know and the other person doesn’t to the common language feels like something… insufficient. Something is always lost, except in the simplest forms of the language. That’s why poetry is untranslatable!

Therefore, whether it’s because you can understand things you wouldn’t if you didn’t speak the language, or for the work benefits of speaking other languages. Or for the romantic benefits (look at me!). Or for the cultural benefits (the latest book from your favorite author hasn’t been translated yet, or you want to understand exactly what Eminem is saying in that controversial song). Whatever the reason, go ahead and learn a new language.

And if in your new adventure you need a teacher for Spanish, English, or Interlingua, or if you’re interested in having a language mentor, send me a message at contact@eduardoortegagonzalez.com

In upcoming articles, I will talk in more detail about the benefits of learning languages, learning experiences, and various strategies you can apply to improve your study of different languages.

Do you plan to start with a new language soon? Let me know in the comments!

(P.S.: this article is a translation. Read here the original in Spanish)